Introduction to SABER Error Covariance Model¶

In variational data assimilation (VAR), the background error covariance matrix B plays an important role in calculating the analysis (i.e., the best guess for the present state given a set of observations). For a linear observation operator \(\textbf{H}\), the analysis \(\textbf{x}^a\) is the sum of the background state \(\textbf{x}^b\) and an update increment \(\delta \textbf{x}\)

where \(\textbf{y}^o\) is a set of observations.

Conceptually, the B matrix contains the covariations in the errors between all pairs of elements in the background state vector (\(\textbf{x}^b\)). So, if a state vector has \(N = 10^9\) entries, the full B matrix will have \(N^2 = 10^{18}\) entries. Storing a matrix of this size in memory is computationally prohibitive, so instead most algorithms implement B as a matrix-like operator which modifies an increment vector.

A conceptual obstacle to understanding the B matrix is that, in a standard frequentist notion, a covariation between a pair of variables is calculated through a sum over some number of matched pairs of draws from the two variables. But, in basic VAR there is only one \(\textbf{x}^b\), so there is only one ‘draw’ and thus no sum over which a covariation can be calculated. Thus, the covariances stored in B are better interpreted in a Bayesian sense as our ‘degree of belief’ and represent the level of uncertainty in the background state of the system: a larger covariance means there is a larger uncertainty in the background state. Covariances are also responsible for spreading information across variables.

Another important consideration to keep in mind about the B matrix is that it is the covariances between errors in state variables. The errors \(\boldsymbol{\eta}\) can be defined as the difference between the “true state” \(\textbf{x}^{\text{t}}\) and the background state, which is our guess for the true state

where it is assumed that the background errors \(\boldsymbol{\eta}\) are unbiased. In practice, we can never actually know the true state. If we could there wouldn’t be a need to do data assimilation! But with this definition we can define B (with a frequentist definition) as

where \(i\) represents a member in an ensemble of \(N\) appropriate ‘guesses’ (or forecasts) \(\textbf{x}^b_i\) for one specific true state. Since the scalar covariance is a commutative operation (i.e., \(\text{Cov}(A,B) = \text{Cov}(B,A)\)), B will be a symmetric matrix (see [Ban08] for more details).

The block chain model¶

Mathematically, a covariance matrix can be split into a correlation part C and a variance part \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}^2\).

The correlation matrix C, in general, is non-diagonal as there could be error correlations between any pair of state variables. \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\), however, is a diagonal matrix with the standard deviations in the errors of each variable along the diagonal.

Generally, it is convenient to work in the eigenrepresentation, a basis in which the error correlations/covariances have been block diagonalized. This can be accomplished with a unitary transformation \(\textbf{V}\) which will transform both the variables and the B matrix from the ‘model representation’ to the eigenrepresentation (indicated with the hats):

Additionally, a balance operator K, a linear transformation which enforces physical constraints (such as hydrostatic or geostrophic balance) is included in the model B [Ban08]. Also, an interpolation operator T may be included to transform from the grid used for modeling B to the model grid. This will make a general model for B a series of matrix multiplications similar to the one shown below:

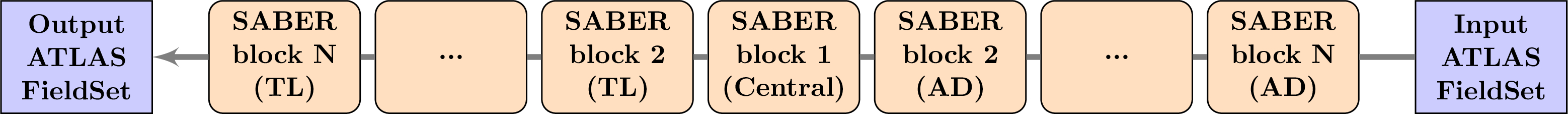

In SABER, the central block C will be present in all block chains (even if it is simply the identity matrix). All the other matrices are referred to as outer blocks, and their transposes are called adjoints (AD).

In the calculation of the analysis increment (see Eq. (41)), B is applied at the front of the expression for the increment vector. In the block chain model, this matrix multiplication is implemented as the application, from left to right, of the series of blocks in Eq. (42). So, first the adjoints of the outer blocks are applied in reverse order. Next, the central block, which is considered to be auto-adjoint, is applied. Then, the direct outer blocks are applied in forward order (indicated as TL: tangent linear):

Block chain specification¶

A SABER block encapsulates a linear operator – which can represent a covariance, transformation, localization, etc. matrix – that is part of the block chain described above (see Eq. (42)).

The list of available blocks for constructing a block chain in SABER can be found in SABER blocks.

A simple model for the background covariance is a B that is constant in time which, in SABER, is an example of a parametric B. Sometimes referred to as a “static” B in the literature, a parametric B could be a fully static model that does not evolve with time or a model that introduces some flow-dependence through dependence on the background state. The implementation of a parametric B will directly match the expression in Eq. (42). Alternatively, B could be modeled with the statistics from an ensemble of forecasts. An ensemble B will allow the background covariances to evolve in time (sometimes referred to as ‘flow-dependence’ or the ‘errors-of-the-day’). Finally, the parametric and ensemble models can be combined into a hybrid B using a weighted sum. These models are described in the following sections.

Parametric B¶

To setup a model for a parametric B, a user must specify their desired sequence of SABER blocks in the yaml configuration file for their experiment following this general outline:

covariance model: SABER saber central block: - saber block name: <central block name> ... saber outer blocks: - saber block name: <outer block 1> ... - ... - saber block name: <outer block N> ...

Each covariance model should have at least a central block, and may or may not have outer blocks. Thus, the simplest SABER covariance model is just the Identity matrix:

covariance model: SABER

saber central block:

- saber block name: ID

Note

A block chain yaml configuration (like the ones above) should be read from bottom-to-top to see the order in which each block will be applied to an incoming analysis increment.

Ensemble B¶

An ensemble B model (\(\textbf{P}^f_{ens}\)) includes a matrix generated from the ensemble members \(\textbf{B}_{\text{ens}}\) and a localization matrix \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{L}}\) which is applied in an element-wise multiplication (a Schur product) to \(\textbf{B}_{\text{ens}}\) to remove spurious covariances between distantly separated grid points [Lor03]:

The setup for a localization matrix is similar to the setup for the parametric

B (described in the previous section) since the computational implementation

of \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{L}}\) and a parametric B are identical.

Both are setup as block chains, but the key difference for a localization setup

is the addition of the localization heading in the localization block chain:

saber block name: Ensemble localization: saber central block: saber block name: <central block for localization> ... saber outer blocks: - saber block name: <outer block for localization> ... ...

When setting up an ensemble model, this configuration of the localization (above) will form the central block inside the full ensemble block chain:

covariance model: SABER ... # ensemble configuration goes here saber central block: # 'outer' central block saber block name: Ensemble localization: ... saber central block: # 'inner' central block saber block name: <central block for localization> ... saber outer blocks: # 'inner' outer block chain - saber block name: <outer block for localization> ... ... saber outer blocks: # 'outer' outer block chain - saber block name: <outer block for ensemble> ... ...

This nesting of block chains can make it difficult to keep track of all the SABER blocks used to make up a covariance model. In this general case (shown above) of an ensemble covariance model, there is an ‘inner’ central block plus associated outer block chain which set up the localization and an ‘outer’ central block plus associated outer block chain (which, for example, could set up an interpolation or variable change). Here is a mathematical outline of the nested block structure:

where the outermost \(\mathbf{T}\) block represents an interpolation and makes up the ‘outer’ outer block chain, the \(\mathbf{V}_l\) represents a variable change and makes up the ‘inner’ outer block chain, and \(\mathbf{C}_l\) is the central block for the localization. The quantities with the \(l\) subscript are part of the full block chain for the localization operator \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{L}}\), and are encapsulated within the ‘outer’ central block in the yaml outline above.

While convoluted, especially to new users, this modularization is a powerful feature allowing for more options and flexibility in building covariance models.

Computationally, in a variational application, the SABER ensemble localization is mathematically applied to the residual vector at the \(k\)-th minimization iteration, \(\delta x_k\), according to the equation:

where \(e_m\) is an ensemble member’s deviations from the ensemble means, and \(N_e\) is the ensemble size.

Note

With settings of covariance model: hybrid or covariance model: ensemble computations will

be done by OOPS. With covariance model: SABER computations will be done by SABER.

Hybrid B¶

A hybrid B is a general linear combination of covariance models. An example of a hybrid B with one parametric component and one ensemble component could be expressed as:

This method is intended to use the strengths of each component model to minimize

the weakness of the others. To set up a hybrid B in SABER, all the components

of the full covariance model will be wrapped into a SABER Hybrid central

block, unless there are outer blocks common to all individual components in which

case those outer blocks could be ‘factored out’ into an ‘outermost’ outer block

chain. See the example below which outlines a SABER hybrid covariance composed

of a static/parametric component and an ensemble component.

background error:

covariance model: SABER

saber central block:

saber block name: Hybrid

components:

- covariance:

saber central block:

saber block name: <central block for parametric>

...

saber outer blocks:

- saber block name: <outer block 1 for parametric>

...

- saber block name: <outer block N for parametric>

...

...

weight:

value: alpha

- covariance:

... # ensemble configuration goes here

saber central block:

saber block name: Ensemble

localization:

...

saber central block:

- saber block name: <central block for localization>

...

saber outer blocks:

- saber block name: <outer block for localization>

...

saber outer blocks:

- saber block name: <outer block for ensemble>

...

...

weight:

value: beta

saber outer blocks: # 'outermost' outer block chain

- saber block name: <outer block common to all components>

Under the components heading in the Hybrid central block, list each individual component

of the full hybrid model, using the dash (-) to mark each new member to the list. Each member in

the list needs a covariance key for specifying the specific covariance model and a weight

key for setting the weight value (e.g., the \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) in (46)) for

each individual component.

SABER allows for a hybrid covariance to contain more than two components (equivalent to adding terms in

(46)). Simply add more members to the list under components:, specifying a

covariance and weight for each member. An arbitrary number of components can be included.

Note

With settings of covariance model: hybrid or covariance model: ensemble computations will

be done by OOPS. With covariance model: SABER computations will be done by SABER.

Geometries used in SABER covariances¶

When used as part of the Variational application, increments input to SABER (and any other implementation of ErrorCovariance) are at the inner loop Geometry, and backgrounds are at the outer loop Geometry. These geometries can be different, often with inner loop Geometry coarser than the outer loop one. By default no resolution changes are performed for the background (to save unnecessary computations), so the background and the increment may be at different resolutions. Yaml key change background resolution can be set to true (default false) to interpolate the background to the same resolution as the increment before applying the SABER covariance, e.g.:

background error:

covariance model: SABER

change background resolution: true

saber central block:

...

saber outer blocks:

- ...

Background and increment geometries can also be changed by certain SABER outer blocks, e.g. blocks performing an interpolation to a different Geometry (e.g. interpolation (shown below) or SpectralToGauss). In this case, the increment’s geometry is changed passing through the SABER block multiplication and its adjoint, and the background’s geometry is changed accordingly if state variables to inverse yaml option specified for this block is not empty.

background error:

covariance model: SABER

saber central block:

...

saber outer blocks:

- saber block name: interpolation

inner geometry:

...

forward interpolator:

local interpolator type: oops unstructured grid interpolator

inverse interpolator:

local interpolator type: oops unstructured grid interpolator

state variables to inverse: # if this key is present with non-empty list of variables all

# variables in the background will be interpolated to the increment Geometry

- stream_function

For the ensemble covariances, the ensemble by default is expected to be on the same Geometry as the increment that is passed to the background error covariance. It is possible to specify ensemble perturbations on an atlas-supported FunctionSpace, by using yaml keys ensemble pert on other geometry (for perturbations) and ensemble geometry (for describing the ensemble’s FunctionSpace). The localization in this case needs to be specified on the FunctionSpace used in the ensemble_geometry yaml section. For example:

background error:

covariance model: SABER

ensemble geometry:

function space: StructuredColumns

grid:

type: regular_gaussian

N: 14

...

ensemble pert on other geometry:

date: ...

members:

...

saber central block:

saber block name: Ensemble

# FunctionSpace-specific localization, not on model Geometry.

localization:

saber central block:

saber block name: ID

saber outer blocks:

- saber block name: spectral analytical filter

...

- saber block name: spectral to gauss

For the Hybrid SABER covariance, one can specify a different model Geometry for different components, using geometry yaml section at the level of covariance components. For example, the yaml outline below has a two-component Hybrid covariance with each component on atlas RegularGaussianGrids with different resolutions:

background error:

covariance model: SABER

saber central block:

saber block name: Hybrid

components:

###########################################################################

# Component 1 - F14 grid

###########################################################################

- weight:

value: 1.0

covariance:

ensemble geometry:

function space: StructuredColumns

grid:

type: regular_gaussian

N: 14

saber central block:

...

saber outer blocks:

...

###########################################################################

# Component 2 - F24 grid

###########################################################################

- weight:

value: 1.0

covariance:

ensemble geometry:

function space: StructuredColumns

grid:

type: regular_gaussian

N: 24

saber central block:

...

saber outer blocks:

...

SABER and 4DEnVar covariances¶

SABER covariances can be used in 4DEnVar applications. For 4DEnVar, the user needs to specify ensembles for each of the subwindows, a single localization for all subwindows for the ensemble covariance, and a single parametric covariance for all subwindows (if using hybrid background error covariances). Parametric block chains (used for ensemble covariance localization and for parametric covariances) take into account time dimension and include time cross-covariances unless otherwise specified.

background error:

covariance model: SABER

time covariance: univariate # optional, default is "multivariate duplicated"

saber central block:

...

saber outer blocks:

- ...

Interfaces¶

All SABER blocks have a constructor that takes as input arguments:

a oops GeometryData,

a list of outer variables,

a configuration with elements on the SABER error covariance,

a set of SABER block parameters (see next section),

a background,

a first guess,

a valid time.

A single Atlas FieldSet is passed as argument for all the SABER block application methods. Blocks are sometimes interoperable in any order. Coordinate transformations and interpolations, however, are not generally interoperable. SABER blocks will implement each of the four following methods (except central blocks which will only implement the first two methods):

randomize: Fill the input Atlas FieldSet with a a random vector of centered Gaussian distribution of unit variance and multiply by the “square-root” of the block. For central blocks only.multiply: apply the block to an input Atlas FieldSet. Required for all blocks.multiplyAD: apply the adjoint of the block to an input Atlas FieldSet. For outer blocks only.leftInverseMultiply: apply the inverse of the block to an input Atlas FieldSet. For outer blocks only.

Other methods are used to glue the blocks together when building a SABER error covariance, from the outermost block to the innermost:

innerGeometryData(): returns the oops GeometryData for the next block. For outer blocks only.innerVars(): returns the oops Variables for the next block. For outer blocks only.

Methods that are only used to calibrate an error covariance model are presented in the section on calibration.

Among the other methods, note that the read() method should be used to read any calibration data, i.e. block data that can be estimated from an ensemble of forecasts.

Base parameters¶

All SABER blocks share some common base parameters, and have their own specific parameters (see SABER blocks). These base parameters are:

saber block name: the name of the SABER block. Only parameter that is not optional.active variables: variables modified by the block. This should include at least the variables returned by themandatoryActiveVars()block method.read: a configuration to be used by the block at construction time. If a configuration is given, the block is used in read mode. Cannot be used withcalibration.calibration: a configuration to be used by the block at construction time. If a configuration is given, the block is used in calibration mode. Cannot be used withread.ensemble transform: transform parameters, for theEnsembleblock only.localization: localization parameters, for theEnsembleblock only.skip inverse: boolean flag to skip application of the inverse in calibration mode. Defaults isfalse.state variables to inverse: state variables to be interpolated at construction time from one functionSpace to another. To be used for interpolation blocks only, when the outer and inner Geometry differ. Default is no variables.

Other parameters related to testing are listed in SABER block testing.