Files and Components¶

IODA data is stored in a hierarchical structure that is quite similar to a filesystem. This filesystem starts at a root path (‘/’), and may contain groups (directories) and data (variables). Groups and data may be created, opened, closed, read, written, renamed, or deleted. Links and mounting are also possible.

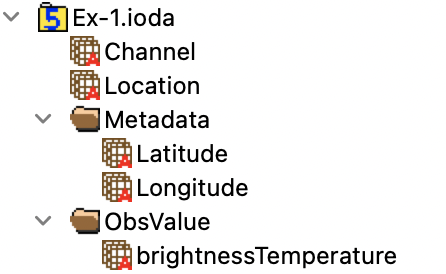

Figure 1 — Schematic view of IODA data showing the hierarchical structure of groups (MetaData, ObsValue) and data (latitude, longitude, brightnessTemperature, Channel, and Location).

The following subsections describe each of the basic components of IODA data. For usage examples, please refer to our Doxygen documentation and GitHub repository. We provide examples for C++, C, and Python.

Files¶

An IODA file is a container for an organized collection of objects. This acts effectively as a self-contained filesystem. In this filesystem, IODA data are organized into a directed graph (hierarchical) structure of objects. Objects can be groups, variables, and links. Objects have distinct, standalone identities in a file. An identifier is a label that points to an object. One or multiple identifiers can point to a single object in the same way that one or more hard links can point to an object in a filesystem.

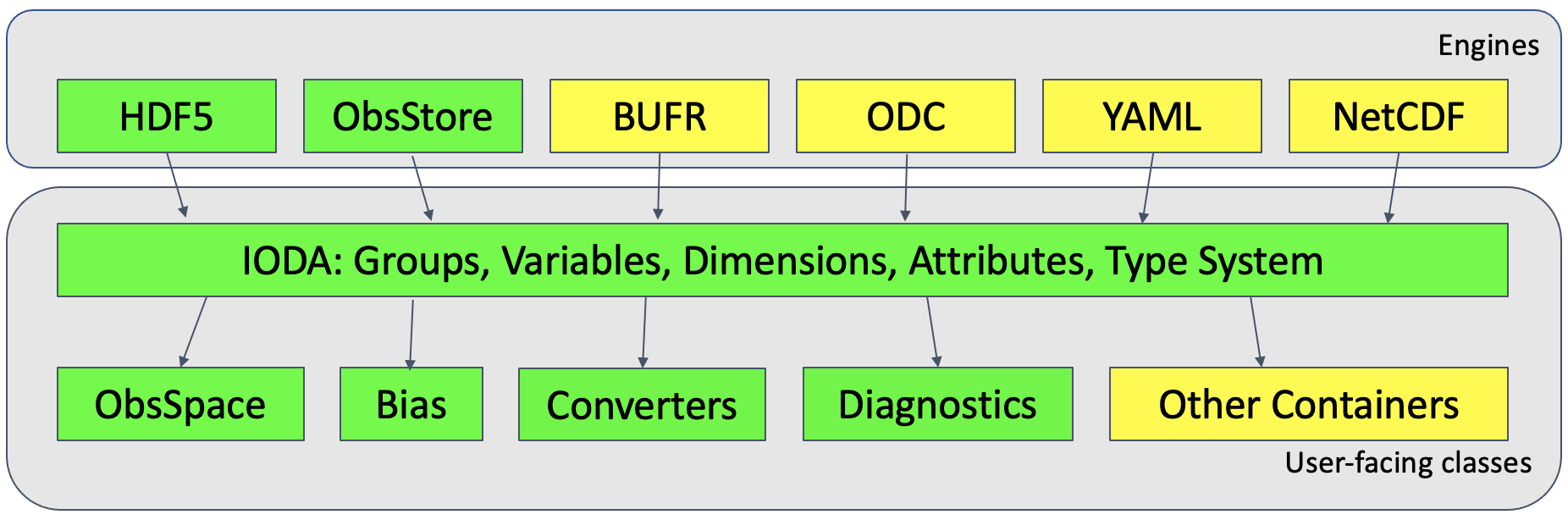

Figure 2 — Various file providers (Engines) can act as data sources to the IODA library, which exposes a set of User-facing classes. Green boxes represent parts of the IODA API that are available in IODA v2.0. Yellow boxes represent work in progress.

Not every “file” is an actual file on a hard disk. IODA can stream objects across a network. Some files exist as in-memory file images that never are written to a disk. Other “files” actually represent entire collections of files on a filesystem; this may be done for performance reasons. IODA files are accessed through the IODA Engines interface (Figure 2), which provides several backends for file access.

IODA files may be written using various backends, such as HDF5, NetCDF, or Zarr. Ideally, access to IODA files should be performed using the IODA library, which can automatically detect the backend format. Eventually, IODA files should end with the “.ioda” extension.

Groups¶

Think of groups as directories or folders. Each group can contain variables, groups, and links.

Groups may contain any number of objects, including zero. No two objects may have the same name in a particular group. Objects in separate groups are unrelated and may share the same name.

Groups use ‘/’ as a path separator. The special path ‘/’ refers to the root group within a file. ‘/foo’ signifies a member of the root group, called foo. ‘/foo/bar’ signifies a member of the ‘foo’ group, which itself is a member of the root group.

In older versions of IODA, ‘@’ was also used as a path separator, but this path separator is read backwards. So, ‘brightness_temperature@ObsValue’ signified an object ‘brightness_temperature’ that was a member of the ‘ObsValue’ group. This convention still works within IODA (it is backwards compatible), however, we do not want newly created data to follow the old schema.

Relative paths are also permitted. Relative paths do not have a leading ‘/’. They are always interpreted relative to the current group.

Unlike most filesystems, there is no ‘..’ object that denotes a parent group.

When searching through a group, both recursive and non-recursive searches are supported. These are implemented in the ‘list’, ‘listObjects’, ‘listVariables’, and ‘listGroups’ methods, which are documented in our Doxygen documentation.

Data types¶

IODA has a rich type system and supports both fundamental data types (integers and floating-point numbers) alongside more complicated objects (array types, strings, compound objects).

Users should consult the variable conventions tables to ensure that they store / access data using the correct type for a particular variable. The tables should be amended if they are incomplete (see section on amending the conventions). By default, data in IODA are assumed to be one of the types in the table below. However, this is entirely customizable, and the full listing is reflected in the “Data Storage Types” page in the conventions tables.

Table 1 — Default (assumed) data storage types

Type |

Default |

C/C++ type |

Fortran type |

Python type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Floating point numbers |

32-bit single precision float |

float |

real, real*4 |

float |

Integers |

32-bit signed integer |

int32_t |

integer*4 |

int |

Strings |

A sequence of variable-length, UTF-8 strings |

std::string |

character |

str |

Enumeration |

32-bit signed integer (see below) |

int32_t |

integer*4 |

int |

The types listed in the variable convention tables reflect the data types used when storing data in IODA. It is always possible to read and write data of a different type. In these cases, IODA will attempt to translate data transparently to/from the internal storage type. A small performance penalty may occur. This is necessary and expected behavior for several reasons. Fundamental data types may or may not be available in different programming languages. Fortran lacks support for unsigned data types. Python has a half-precision (16-bit) floating point type that is unavailable in C++. Different systems have different endianness. Different CPU architectures use slightly different representations of floating point numbers, and the float representations do not always have the same range or degree of precision. If IODA is unable to convert data between the user-requested type and the storage type, then an error will be returned to the caller.

Floating point numbers should only store valid numeric values. NANs, +- infinity, and other similar flagged values are not portable across systems and must not be used. Missing data should be tagged using the appropriate fill value for the data type. See the Missing Data section of this document for guidelines.

Strings are complicated. Strings can be either fixed-length or variable length. They can store data in ASCII, UTF-8, UTF-16, or UTF-32. Historically, “code pages” were created to map a wide range of character encodings into a smaller set of values. Individual characters can be represented either using wide or multibyte characters. C++20 recently has attempted to add a new “char8_t” type to help disambiguate regular single-byte data (type char) from UTF-8 data. We assume that all string data in IODA is UTF-8. Variable-length strings are preferred unless there is a performance issue, in which case a fixed-length string type should be used.

Occasionally, some of the types in the table overlap. This is particularly noticeable for enumerations and integers. We support custom enumerated data types that represent categorical data, such as land surface types, weather types, cloud types, sea states, and so on. The IODA file format should be self-describing, without strong dependencies on the IODA code. As enumerations are intrinsically non-portable, the type definitions will be encoded into IODA files. IODA support is anticipated soon, and examples are forthcoming.

Bitsets and compound data types are anticipated, but are not yet implemented. They will have their own custom types.

The type system is intrinsically tied into data access. For examples of how to read and write different data types, refer to the “Attributes” and “Variables” examples in the subsequent sections of this document.

Variables¶

Variables store data using rectangular, multidimensional arrays.

Variable names are standardized in the conventions tables. Variable organization is described below, in the IODA Objects and Layouts section.

The dimensionality of a variable is set on creation time, as are initial lengths along each dimension axis. Some axes can be marked as resizable upon creation.

The data type of a variable is also set at creation time. The data type cannot be changed after variable creation. This data type represents the type used when storing the variable’s data. Data type conversions can occur when a user reads or writes to a variable. For example, a user can create a 32-bit signed integer variable and can write 16-bit unsigned integers to it. Or, a user could write doubles and read floats. These conversions are performed automatically. Conversions are also expected because different machine architectures and programming languages implement numeric types slightly differently.

When reading or writing a variable, you do not need to read or write the entire variable. IODA provides selection operators to specify subsets of data.

Variables may be stored in small, contiguous blocks (also called chunks) within a file, rather than having the variable occupy one contiguous region within a file. This allows us to efficiently resize and append to data without having to deal with excessive file fragmentation and repacking performance issues. Chunked variables may be compressed. The zlib and szip compression libraries are implemented, and additional compression algorithms are easily possible.

Variables are expected to contain attributes and will have a dimension scale attached to each dimension axis. Both attributes and dimension scales are described below.

Variables may also have a “fill value” that denotes empty values within the data. We do not standardize what a “fill value” means. It can denote missing observations within the data. It can also represent areas of a file that were never written (such as immediately after resizing or creating a variable). The default fill value is described in the Missing data and fill values section of this document, but this value may be overridden during variable creation. Once set, this value cannot be changed.

Attributes¶

Attributes convey supplementary information about a variable or a group. They share many of the same characteristics of variables. Each attribute has a name, a data type, and dimensions. Attributes are distinct for each variable or group. Names may be reused across variables. That is, Variable “A” and Variable “B” may each have their own distinct attribute named “Units”.

Common attribute names are standardized in the conventions tables.

Attributes are intended to be smaller than variables. Unlike variables, attributes are written using contiguous storage. Partial reads and writes are not possible. Compression does not occur. Attribute dimensions do not have attached dimension scales.

In IODA 2.0, attributes should have either zero dimensions (i.e. contain a single value) or one dimension (i.e. a vector of data). This limitation is imposed by NetCDF, which is still used for some diagnostic tools within the JEDI system.

Dimension scales¶

A dimension scale is a special type of variable that helps users understand the scientific space of a variable. A dimension scale may be used to represent a real physical dimension, such as time, latitude, or longitude. It can also index abstract quantities, for example, an instrument channel number, a model’s atmospheric layer number, or a location ID.

A variable may have any number of dimensions, including zero, which makes the variable a scalar. The dimensions of the variable define the axes of the quantity it contains. IODA variables should generally have a single dimension scale attached to each dimension. So, if a variable has three dimensions, then it should have three attached dimension scales.

Every dimension scale has both a name and a size. The name is a label for user convenience. The size is a non-negative integer, and it should be sized as follows:

Generally, the size of a variable’s axis should match the size of the attached dimension scale. For example, if a variable has a dimension of “ATMS Channel Number”, and “ATMS Channel Number” has a size of 22, then the variable should have 22 elements along that dimension.

Future IODA release: A dimension scale may contain either zero elements or one element. This denotes a placeholder dimension. Usually, an auxiliary coordinate variable is available to provide meaning to the dimension. For example, assume that a “Radiance” variable exists, with a dimension of “Channel”. The “Channel” variable might be entirely empty. However, parallel variables like “Channel Center Frequency” and “Polarization” might also exist that provide context to the “Radiance” variable.

Future IODA release: A dimension scale may be Unlimited, in which case it has an arbitrary size.

Dimension scales do not need to contain data. They can be filled with zeros. This is because auxiliary coordinate variables can be used to provide meaning to the dimensions. See the Coordinate Systems section of this document for examples.

Dimension scales should be located at the roots of IODA objects (see below).

Links (future IODA release)¶

These behave like links in a filesystem. Links may be hard links, symbolic links, or external links. All objects (variables, dimension scales, groups, and other links) are valid targets for all types of links. Circular directory hierarchies are possible with links, so when listing or enumerating objects users should use the built-in “listObjects” functions which already have proper recursion support. Links are experimental and will be developed in a future IODA release. They are mostly undocumented.

Mount points (future IODA release)¶

These behave like mount points in a POSIX filesystem. This feature is experimental and will be developed in a future IODA release.